CWN#2: Newly translated horror // Dongbei Renaissance, part 1

Featuring Ban Yu 班宇 and Yang Zhihan 杨知寒

Welcome to the second issue of the Cold Window Newsletter. This time: a great new speculative fiction anthology; a first foray into one of the liveliest scenes in contemporary Chinese literature; and a look back at the year’s notable Northeastern Chinese fiction.

PSA: Sinophagia is genuinely unsettling

In case you missed it, Sinophagia, the long-awaited anthology of Chinese horror fiction edited and translated by Xueting C. Ni, came out from Solaris this fall. As I expected, it fits snugly into the emerging canon of recent, high-quality anthologies of translated speculative fiction. Not as I expected—although I should probably have seen this coming—it’s pretty terrifying. Be prepared for gore. Be prepared for gruesome psychological manipulation. It's terrific. The blunt emotive force of the best of these stories is exactly why they’re worth your time.

Ni writes in her introduction that there’s little recognition of the horror genre as a meaningful category in China, even among the writers who seem to belong to it. The term that she ultimately settles on to describe the stories in this anthology is kongxuan 恐悬, a combination of the words for “horror” and “suspense.” But what comes across most clearly is the sheer diversity of stories that have emerged from the impulse to scare in the absence of set genre boundaries. There’s campus horror centered around urban legends in college dorms (“The Girl in the Rain” 《雨女》 by Hong Niangzi 红娘子). There’s science-fictional workplace horror (“The Waking Dream” 《清醒梦》 by Fan Zhou 范舟, which you can sample here). There are a number of ghost stories that might feel like traditional Ming-dynasty folk tales if they weren’t so bloody. Ni notes that some of the authors in this collection have been friends or colleagues with each other for years but have never appeared together in a print anthology before now. That’s just another thing making the existence of this book in English feel like a small miracle.

Profiles: Welcome to the Dongbei Renaissance

The term 东北文艺复兴 (Dongbei Renaissance, where Dongbei refers to China’s culturally and geographically distinct northeast) has been inescapable in certain corners of the Chinese literary internet over the last few years. As far as I can tell, it doesn’t have a universally agreed-upon meaning. In some cases, it seems to refer to a small handful of young novelists whose work is based in Dongbei linguistic patterns and recent history; in others, it encapsulates the whole sweep of Dongbei cultural production from recent years, including film and music from the region, which have become increasingly popular in the rest of China. What’s clear is that many of the most acclaimed younger novelists and artists in China not only hail from the northeast, but choose to specifically highlight the region in their work.

And yet attention to this trend has been scarce in the English-speaking world. Shuang Xuetao 双雪涛, probably the best-known of the younger generation of Dongbei novelists, has enjoyed a rising international profile thanks especially to Jeremy Tiang’s 2022 translation of his collection Rouge Street (collecting three novellas originally published separately in Chinese). Other translations, mostly of short stories by the region’s two or three best-selling authors, have emerged at a trickle. The vast majority of contemporary Dongbei literature remains totally untapped in English.

If you’re looking to get started reading new Dongbei fiction—or, frankly, new fiction from China as a whole—there’s hardly a better place to start than with Ban Yu 班宇. For one thing, Ban Yu is a genuine literary star, hailed (along with Shuang Xuetao and Zheng Zhi 郑执) as one of the “three swordsmen west of the tracks” (铁西三剑客) whose style defines the Dongbei Renaissance. He’s long overdue for attention in the West (although a translated collection is reportedly in the works). For another, the quality of his writing has remained remarkably consistent across the three collections of stories he’s published so far, so that you can be confident that you’re in good hands whether you’re reading about a sentient ant farm (“The Antman” 《蚁人》), a small-time crime spree (“Gun Grave” 《枪墓》), or a town leaning ever so slightly to one side (“Stepwise Sunset”《梯形夕阳》). As an added bonus, he makes a point of achieving emotional depth through clear, stark, simple language, which makes his writing more approachable than some of his peers if you’re not a native reader of Chinese.

As a longtime fan of Ban Yu’s work, I have a soft spot for Winter Swim 《冬泳》, his 2017 debut collection. The author made his name on the basis of these jagged, matter-of-fact stories about fathers and sons navigating the harsh landscape of postindustrial Shenyang. As you move through the collection, plot points echo from one story to the next; mothers vanish; fathers scramble for money and clash with the law; encounters with the frigid, unyielding northeastern landscape prompt flashes of lyricism that burst from the page like fireworks. Go read the title story, “Winter Swim”《冬泳》, which was translated for the Leeds Centre for New Chinese Writing Book Club by Guo Huarui and Helen Lewis with Chen Xiaonan. For a more academic introduction to Winter Swim, Qi Wang also has an excellent article that runs through the symbolism of the landscape in each story.

But my best advice, if you’ve never read Ban Yu before, is to seek out the title story of A Slower Pace 《缓步》, his most recent collection, from 2022. Since Winter Swim, Ban Yu has branched out somewhat from his old theme of boyhood in Shenyang, and “A Slower Pace” reads like a mature writer revisiting the material that defined his early career. The story follows a single father as he learns to raise his daughter alone, thinking constantly about the wife who abandoned them and yet unable to resent her for doing so. As in the best of Ban Yu’s work, there are stories within stories, and ambiguous encounters with mysterious strangers. And, as in the best Ban Yu Stories, the narrator’s desperation to be a good person shines through the darkness.

Ban Yu 班宇

Born 1986

Paper Republic

Recommended story in Chinese: 《缓步》(excerpt)

Available in English: “District Champ” 《铁西冠军》(full story); “Winter Swimming” 《冬泳》(full story); “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” 《肃杀》(excerpt & purchase)

Ban Yu is a novelist from Shenyang. He has published the story collections 《冬泳》 (Winter Swim), 《逍遥游》(Carefree Journey), and 《缓步》(A Slower Pace).

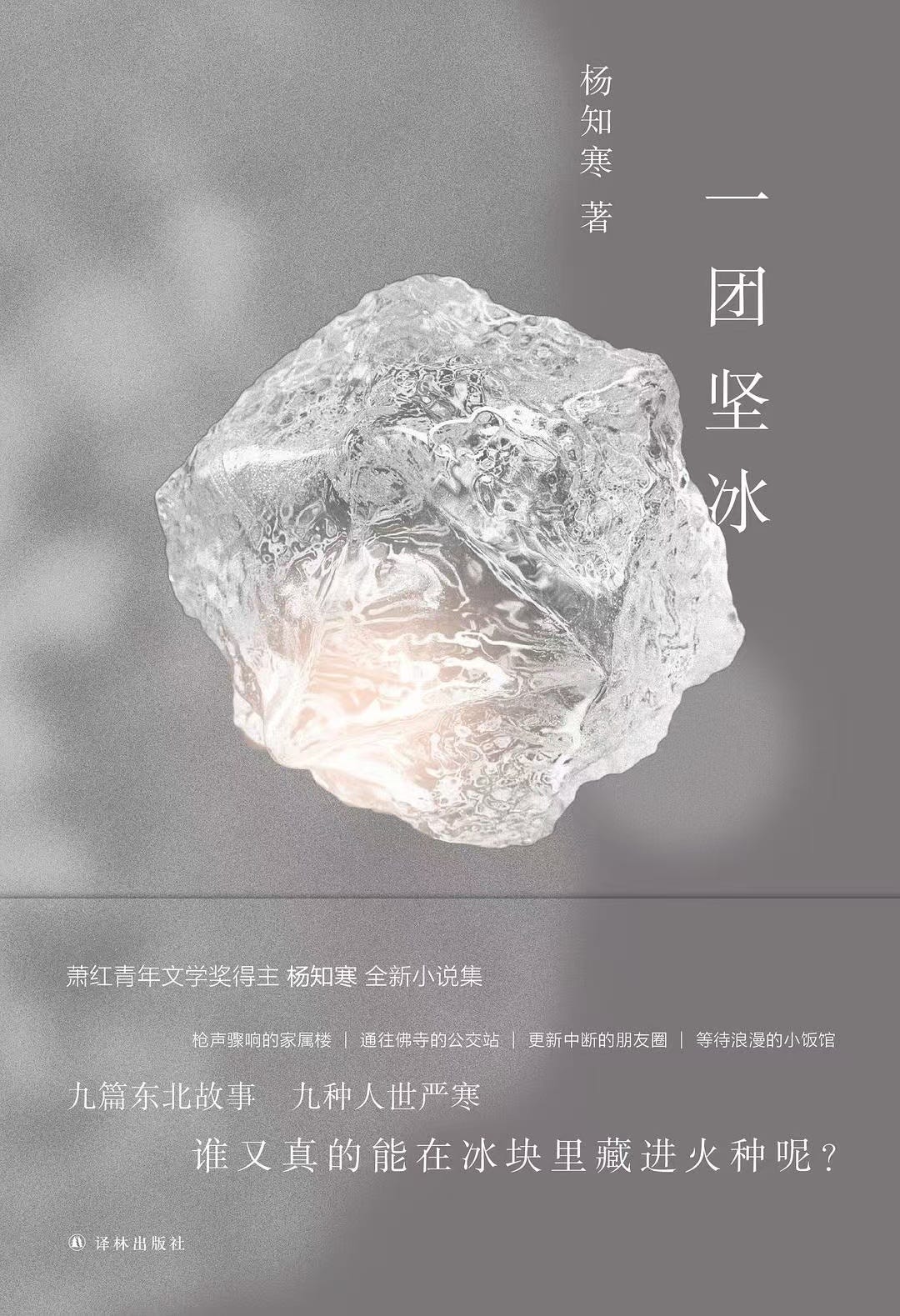

The stories of Yang Zhihan 杨知寒 aren’t brought up as often in connection with new boom in Dongbei literature as those of Shuang Xuetao and Ban Yu, but they should be. Yang was only in her twenties when she released her debut collection, A Solid Clump of Ice 《一团坚冰》, which went on to win the 2023 Blancpain-Imaginist Literature Prize. Since then, she’s received endorsements from critics like Chi Zijian and David Der-wei Wang and released two more collections, the most recent of which, Fishing Alone 《独钓》, came out just this past month.

Yang Zhihan’s writing shares the same short, icy sentences and penchant for local dialect that mark other Dongbei literature of her generation. But where Ban Yu often follows a dream logic that leads his narrators stumbling from one mysterious encounter to the next, Yang’s stories are more often rooted in concrete human relationships, and a surprising tenderness can arise from her stark prose. Consider “The Flooded Bridge” 《水漫蓝桥》, my favorite of her stories, which follows a bad-tempered line cook and a downtrodden opera singer who insists on ordering the most complicated dishes on the menu:

师傅,你是这一年里,给我做这俩菜的第一个厨子。我感谢你。谢你给我留了念想。人能找着个等的地方,也是种幸运。我起了兴趣,凭点俩菜就敢找人,敢死等,浪漫病晚期啊。我这也不是治病的地方。问他,还有什么凭证?他手指落桌面,轻点两下,哼出句九曲十八弯,等在蓝桥啊——

“Sir,” he said, “you’re the only cook I’ve found all year who will make these dishes for me. You have my thanks. For returning my memories to me. It’s a fortunate thing, to find a place where one can wait.”

This caught my interest. If he was trying to find someone simply by ordering these old dishes, if he was willing to wait for her till death, then he must be suffering from terminal heartsickness. And I’m not in the business of curing the sick.

“How else will you know it’s her?” I asked.

He tapped lightly on the table, twice, and began to hum a meandering tune: “Upon the bridge I wait for you—”

In the figure of the romantic, dissipated singer, Yang might be channeling Kong Yiji, the classic pedant from Lu Xun’s story who hangs around wine halls pining for a past that will never return. Even more than Lu Xun, though, she’s taking the Northeast itself as her source material: its cuisine, the rhythms of its language, the cramped interiors of its family-owned shops on winter nights. She’s attuned to the ways that small collisions in these narrow spaces can blossom into friendship, as between the elderly widow and widower in “Thirdhand Sedan” 《三手夏利》, or curdle into hatred, as in the frigid crime story “Repossessions” 《连环收缴》. Yang is interested in the potential for human connection between strangers, but she never shies away from revealing the darkness at her characters’ core.

Yang Zhihan 杨知寒

Born 1994

Paper Republic

Recommended stories in Chinese: 《水漫蓝桥》(full story); 《三手夏利》(excerpt)

Available in English: “Hai Shan Swimming Pool” 《海山游泳馆》(excerpt & purchase); 2024 interview at the Northeast Asia Art Archive

Yang Zhihan was born in 1994. Her writing has appeared in People’s Literature, Dangdai, and Huacheng. She is the recipient of the People’s Literature Newcomer Award, the Sinophone Youth Author Award, and the Blancpain-Imaginist Literature Prize, and she was named one of the best young writers of 2023 by Zhongshan Magazine. She has published the collections《一团坚冰》(A Solid Clump of Ice), 《黄昏后》(After Dusk), and 《独钓》(Fishing Alone).

Review Roundup: 2024 in Dongbei Fiction

The Dongbei canon continues to grow. Here’s a snapshot of some of the fiction published by big names in Northeastern literature during the last year—coincidentally, all short story collections. I haven’t personally read the books below, but I’ve translated some snippets from professional and amateur reviews so that you can get a taste of what the Chinese internet thinks of each one.

In January, Chi Zijian 迟子建, one of the most decorated writers in China, came out with Stories of Northeast China 《东北故事集》, a collection of three novellas. The top review on Douban, by “尤里卡,” sees Chi’s Northeast as an alternative to the stark landscape portrayed in fiction by the younger writers of the Dongbei Renaissance: “To read this book is to encounter not only the author, but also a whole different face of the Northeast, one that hides in the mists of history, colored by fantasy and mythology... The author’s delicate prose glows with a completely new kind of liveliness and charisma. It showed me a different Dongbei from those typical tales of unemployment, crime, and ordinary folk.”

February saw the release of Shuang Xuetao’s newest collection, Uninterrupted People 《不间断的人》. In citing it for Harvest magazine’s annual best-books list, Huang Dehai wrote: “Uninterrupted People takes our daily lives as its starting point and expands inexorably into worlds beyond our awareness. The narrative expansions might feel disconnected from each other, but one by one they are tightly welded into a whole. Experience and imagination, humanity and technology, reality and invention—all ultimately become difficult to differentiate, bound together in an intricate experiment into the possibilities of fiction.” (Also see this review in English from World Literature Today.)

As mentioned above, Yang Zhihan has a new collection called Angling Alone 《独钓》 that came out in June. The Dazhong Daily was impressed: “The book is a continuation of Yang Zhihan’s signature style, icy and sharp but not lacking in humorous detail. Once again set against the backdrop of the Northeast, it presents the stories of ordinary people living their absurd lives and laughing through their tears.”

And finally, there’s a new collection out from Zhao Song 赵松, an excellent (and rarely translated) writer from Fushun who deserves his own profile one day. The book is called You Head into the Wilderness 《你们去荒野》, and, according to the novelist Wang Suxin 王苏辛, reading it is like “looking at an exhibition of oil paintings. Heavy colors stretch over the canvas, the brushstrokes only visible when you look closely; from afar, you can make out a human being, but up close all you see are blocks of color.”

That’s all for this issue. Next time: a look at the young writers highlighted in this year’s most prestigious fiction prize. See you then!