CWN#1: Welcome // New stories from Shanghai // Literary deaths of 2024

Featuring Gu Xiang 顾湘 and Wang Zhanhei 王占黑

Welcome to the pilot issue of the Cold Window Newsletter. This week: what this newsletter is all about; a pair of short-story writers from the vanguard of Shanghai literature; and a look back at two major authors who passed away earlier this year.

Introduction: What is the Cold Window Newsletter?

The idea for this newsletter came from my observation, years ago, that there are hardly any spaces on the English-language internet dedicated to discussing, reviewing, or recommending new Chinese writing. For those of us who are interested in Chinese literature but do most of our reading in English, it’s hard to get a sense for what the Chinese literary world is buzzing about at any given time. And while excellent projects like Paper Republic, Spittoon, and the Leeds Center for New Chinese Writing Book Club can give you a snapshot of fiction from China that has already been translated into English, where can you go to hear about Chinese fiction that is still too new to be translated, or that may already have been waiting for years for the right translator to come along?

Thus was the Cold Window Newsletter born.

Who this project is for:

Literature fans who want to join the conversation about emerging writers and works in China. The vast majority of the younger generation of Chinese writers have never been written about in English before—not in the news, not on Wikipedia, not in academic journals, not on web forums... I envision this newsletter above all as a small corrective against that fact, a biweekly bulletin about writers who might not have crossed your path otherwise. Even if you regularly follow Chinese literary news, you can always use more help to sort through the noise and discover genuinely exciting new voices. I’ll also provide occasional updates about major literary awards, deaths, and news stories that can guide your exploration further.

Translators in search of overlooked writers who deserve exposure abroad. Despite the heroic efforts of translators and venues like Paper Republic, a small handful of major writers continue to make up the bulk of stories from China that are translated into English. We all benefit when more stories, and more diverse stories, are available to enrich our understanding of other places. I’ll focus on writers whose works have rarely or never been translated into English before, and I’ll give a rundown of any coverage they may have received in English to date.

Advanced language learners who advice on which stories to read. If Chinese isn’t your first language, it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the sheer breadth of fiction out there. Doing deep dives into the back catalogs of every potentially interesting author isn’t a realistic option if your reading speed in Chinese is slow (I would put myself in that camp!). I’m hoping that these profiles will help you figure out which pieces you might be interested in before you start reading, so you don’t have to dive in blind.

Some promises and disclaimers:

This newsletter will mostly focus on short fiction, but look out for occasional roundups of new poetry, essays, online fiction, etc. as well. Coverage of long-form fiction will be sparser, as it’s hard to read large numbers of novels fast enough to review and recommend them in regular installments. Still, when profiling new writers, I’ll make sure to provide a rundown of their longer works alongside my recommendations of shorter works.

I’ll be up front about which works I’ve read, and which I know just by reputation. I won’t recommend books that I haven’t read myself.

The format of this project is indebted to several excellent preexisting newsletters that focus on contemporary art and media in China, including Jake Newby’s Concrete Avalanche, Michael Hong’s Mando Gap, and Em’s Active Faults (not to mention the late great Chaoyang Trap). I also want to recommend Na Zhong’s “What China’s Reading” column at the China Books Review, which has been one of the best places to learn about new literary releases in China since she started writing it last year.

Feature: New short stories about a changing Shanghai

Among the younger generation of writers, you’d be hard-pressed to find any who are more attuned to the rhythms of Shanghai life than Gu Xiang and Wang Zhanhei. Both writers have garnered increasing acclaim for short stories that, among other things, depict elderly Shanghai residents struggling to carve out a space for themselves in a world that seems all too willing to leave them behind.

In her deceptively simple short stories, Gu Xiang 顾湘 (born 1980) approaches Shanghai with the careful eye of a naturalist. Among the snapshots of modern Shanghai life you might encounter in her fiction: a herd of commuters groping their way by flashlight through a darkened subway station; a hospitalized women desperately peering at her beloved pet rabbit through a video feed on her phone; a family recipe for Shanghai-style borscht, passed down from the era when the city hosted large populations of Russian and Eastern European immigrants.

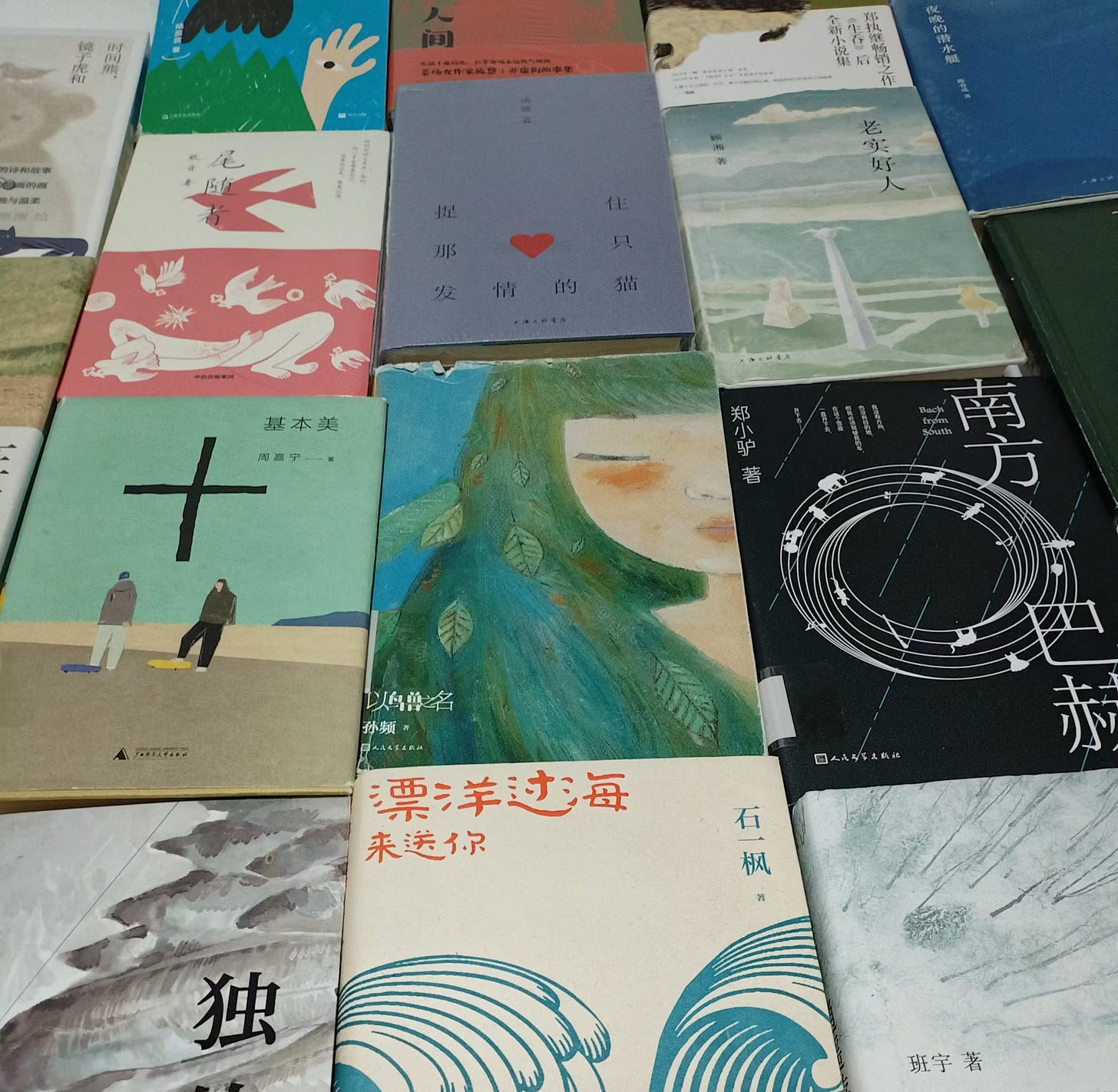

The place to start with Gu’s fiction is her most recent collection,《老实好人》(Good, Honest People), which was named one of Douban’s Top Books of 2023 and is shortlisted for this year’s Blancpain-Imaginist Literary Prize (winner to be announced on October 21!). The stories are lucid and easy to read, often following elderly protagonists whose blithe narration disguises deep feelings of loneliness and alienation from the evolving city around them. This is especially the case in the sparkling《和平公园》(“Heping Park”), in which the intensely private life of a middle-aged gay man is shattered by a random act of kindness in a park and the arrival of a pet rabbit in his home. Another story exploring the psychology of Shanghai seniors, 《敬老卡》(“June 23, 2016”), was translated for The World of Chinese by Jesse Young in 2021, making it the only piece by Gu Xiang that is currently easily accessible in English.

It's well worth getting your hands on a physical copy of Gu’s books if you can, as the dreamy paintings she composes for their covers and frontispieces tell stories all of their own. Good, Honest People bears a drawing of the titular playground sculpture from《球形海鸥》(“A Spherical Pelican”), one of the darkest stories in the collection, about a literature student whose façade of cheerfulness begins to break down as she pursues a relationship with a death-obsessed young man in Japan. (Gu has cited this as her personal favorite piece in the collection.) It’s also worth checking out her earlier collections of personal essays, 《赵桥村》(Zhaoqiao Village, 2019) and 《在俄国》(In Russia, 2020), the latter of which contains some of the best reflections on the simultaneous exhilaration and loneliness of studying abroad that I have ever read.

Gu Xiang 顾湘

Born 1980

Paper Republic

Recommended stories in Chinese: 《和平公园》(excerpt); 《球形海鸥》(excerpt)

Available in English: “June 23, 2016,” translated by Jesse Young (read); “The Cat,” translated by Natascha Bruce (purchase)

Gu Xiang received a bachelor’s degree in playwrighting from Shanghai Theatre Academy and a master’s degree in journalism from Moscow State University. She is a writer and artist. Her works include the essay collections 《好小猫》(Good Kitty), 《赵桥村》(Zhaoqiao Village), and 《在俄国》(In Russia); the short story collection《为不高兴的欢乐》(Toward an Unhappy Joy); and the novels 《西天》(The Western Sky) and 《安全出口》(Safety Exit). She has translated Alice in Wonderland and Treasure Island, and she collaborated with 范晔 Fan Ye on《时间熊,镜子虎和看不见的小猫》(Time Bear, Mirror Tiger, and the Invisible Cat), among other works.

Like Gu Xiang, Wang Zhanhei 王占黑 (born 1991) is interested in elderly urban residents struggling to maintain their way of life. But whereas many of Gu’s stories highlight the loneliness of life in Shanghai today, the early story collections for which Wang is best known, 《街道江湖》(Neighborhood Adventurers, 2018) and《空气炮》(Air Cannon, 2018), are suffused with a sense of whimsy and affection. I first became aware of Wang when a piece from Neighborhood Adventurers, 《阿明的故事》“The Story of Ah-Ming,” was included in The Book of Shanghai in a translation by Christopher MacDonald. The story, which revolves around the familiar sight of retirees picking through trash bins for items to repurpose or exchange for money, is largely tragic, but the irrepressible personality of the close-knit, gossipy community where Ah-Ming lives still shines through. For a sense of this in Chinese, I recommend 《香烟的故事》(“The Story of the Cigarette”), from the same collection, which also takes community love and support as a theme even as it chronicles the decline of yet another member of Shanghai’s vanishing older generation.

I detect a slightly darker turn in Wang’s third collection, 《小花旦》(Dame, 2020). The stories remain rooted in the specificities of traditional enclaves within urban spaces—insular, aging, resistant to change—but Wang appears more willing to bring the negative aspects of these communities to the fore.《清水落大雨》(“A Deluge of Clear Water”) follows Qingshui, a young woman whose inner fire has been stifled by the ceaseless dampness of the Shanghai climate and a lifetime of friction with her family. I have not gotten my hands yet on 《正常接触》(Ordinary Contact), Wang’s new collection out this fall, but I will be interested to see if it continues this turn away from lovingly crafted neighborhood tales.

Wang Zhanhei 王占黑

Born 1990

Paper Republic

Recommended stories in Chinese: 《香烟的故事》(excerpt); 《清水落大雨》(excerpt)

Available in English: “The Story of Ah-Ming” (excerpt; purchase); 2018 profile from Neocha

Wang Zhanhei was born in 1991 in Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province. She was the winner of the inaugural Blancpain-Imaginist Literary Prize. She has published the story collections 《空气炮》(Air Cannon), 《街道江湖》(Neighborhood Adventurers), 《小花旦》(Dame), and 《正常接触》(Ordinary Contact).

In Memoriam: Chi Pang-yuan and Shen Rong

Hardly breaking news, but the first few months of this year saw the passing of two major Sinophone authors who deserved more coverage in English than they received. Perhaps the better-known of the two outside of China is Chi Pang-yuan 齊邦媛, an author and translator who worked for decades to bring greater international exposure to Taiwan literature. Her classic memoir 《巨流河》(The Great Flowing River: A Memoir of China, from Manchuria to Taiwan, 2009) is available in an English translation by John Balcom—check Bookshop, or the digital collection of your local library. I’ve only read part, but it provides a fascinating window into the turmoil that the Chinese intellectual world was thrown into during the upheavals of the mid-twentieth century. Chi was 100 when she died on February 19 of this year.

Even more relevant to the mission of this newsletter is Shen Rong 谌容 (sometimes referred to in English as Chen Rong; the surname is pronounced Shen in Sichuan dialect but more typically Chen in Mandarin). Shen, who died at the age of 88 on February 4, is recognized within China as a major author on largely rural themes, but her work has never received much attention in the English-speaking world. Despite writing prolifically up until her death, none of her work has been made available in English since the 1970s and 1980s, when she produced her most famous work, the novella 《人到中年》(“At Middle Age”). It’s well worth tracking down the novella and giving it a read, either in the anthology Roses and Thorns or in one of those strange translated collections put out in the late ’80s and ’90s by Panda Books.1 The story follows a female optical surgeon pushed to the brink by the combined pressures of her work and family, and it feels shockingly modern for a story published in the very early days after the end of the Cultural Revolution. Hopefully Shen’s passing will not stop translators from bringing more work from her long career into English.

That’s all for this issue. Next time: the Dongbei Renaissance, and a look at a brand-new anthology of translated fiction. Thanks for reading!

I’m fascinated by these Panda Books and Foreign Languages Press editions. They were clearly state-affiliated, but who were they made for? Did anyone actually buy them? Who were the translators? There are thousands of pages of these books available for free online, and while their quality varies drastically, they’re great for filling in gaps in the oeuvres of famous writers who might otherwise have had only one or two stories come out in English.

Absolutely LOVE this project and thanks for the shoutout! I try to binge-read and play catch up with the latest literary breakout stars every time I go back to Beijing. Here are two of my recent favourites: 陈春成‘s 夜晚的潜水艇, 焦典's 孔雀菩提, and both are just so playful and masterful with the Chinese language. Can't wait to read their future works.