CWN#7: The fractal madness of internet literature genres

13 Ways of Looking at Chinese Internet Literature (#3-4)

Welcome back to the Cold Window Newsletter! In this issue, the long-delayed return to my series on Chinese internet literature, with a focus on the chaotic sprawl of genres within which online fiction is produced. There’s a lot to say, so I’ll be splitting it up into two posts, published a week apart. No author profiles or recommended stories this time, but look forward to a bunch of those in a seasonal special later this summer.

I made this disclaimer last time, but it bears repeating: Chinese internet literature is one of the most massive media ecosystems in the world, and I am as far as can be from an expert. If you, like me, are a newcomer in this world, let’s treat this series as an opportunity to learn about it together. And if you’re a long-standing fan, I hope you’ll lend your expertise to the conversation.

Thirteen ways of looking at Chinese internet literature: Genre madness (3-4)

The first Chinese internet novel I ever really got into was about video gamers in a post-apocalyptic world. (I will withhold the title of the novel out of embarrassment.)1 A game-master transports them into the wasteland under the pretense that they are playing a VR game, and by manipulating them with quests, meaningless digital currencies, and promises of exclusive rewards, he manages to build an unstoppable army of blithe gamer warriors willing to carry out his every whim. I was astonished by the creativity of the concept: its humor, its moral ambiguity, its blending of classic sci-fi with manga tropes and game mechanics... It wasn’t until hundreds of chapters in that I discovered that this exact blend of story elements has a name: “Fourth Calamity” 第四天灾 fiction, so called because the arrival of gamers who fear no death and are hungry for loot on an unsuspecting world is an epoch-scale calamity. The Fourth Calamity subgenre is a tiny sliver of the video game novel subgenre, which is only part of the sci-fi and system story (系统文) genres. Novels in this subgenre operate in an incredibly specific range of plots.2 And yet there are a lot of them.

Chinese internet literature is VAST. All it takes is a quick scroll through Qidian or Novel Updates to see the whole bedazzling landscape of genres and subgenres unroll before you. But you’re not likely to learn much about internet literature as a whole just by gawking at genre names. Part of my thesis in this series is that internet literature cannot be understood at a glance (it takes at least thirteen!), and that goes for internet genres as well. So, for our next four Ways of Looking, we’ll try to approach genre from a handful of different perspectives. This week, in Part 1, a lexicon of how genres are talked about, and a bird’s-eye view of why they matter. And in Part 2 a week from now, a basic taxonomy of the genres themselves, and a blitz through some of the classic works that define them.

Let’s get to it. Check out my post from May if you want a refresher on Ways #1 and #2.

Way #3: as a new way to talk about literary pleasure

Like any subculture, internet literature fandom has a vocabulary of its own that can be intimidating for those outside of it. Without getting into genre-specific terminology, I want to give a quick introduction to the words that fans use to talk about what they like and what they don’t. If you want to understand genre, that’s where you have to start. After all, genre itself is just a tool to tell you what pleasures to expect from a novel and how they will be delivered.

爽 (shuăng). Shuăng is the feeling of pleasure that you get from sliding effortlessly through a novel. You often see it described in drug terms: it’s an addictive high that wears off over time if an author doesn’t constantly come up with new ways to stimulate it. 爽点 (pleasure points) are the parts of a novel that compel you to return to it obsessively, and 爽文 (pleasure lit) is a slightly dismissive term for novels that only exist to take you from one pleasure point to the next.

嗑CP (ship). A CP is a pair of preexisting characters, and for a fan to嗑 them is to ship them together. Thus is a fanfiction born. 嗑CP is one of the main ways that fans (especially female fans) engage with internet media as both readers and writers, and is therefore one of the most powerful engines of internet literature and of Chinese pop culture as a whole. More on this in a future installment.

男频、女频 (male-channel and female-channel). The marketing of modern internet novels is extremely gendered. Novels and even entire genres and platforms are categorized as “male-channel” and “female-channel” based on the assumed gender of their authors and audience. These terms can carry a slightly derogatory implication of pandering shallowly to male or female readers’ base desires. It’s a problematic binary, because internet novel authorship and readership are both more diverse than these terms make them seem. More on this later too.

穿越 (transmigration). A ubiquitous starting point in modern internet novels, both male-channel and female-channel. The protagonist suddenly wakes up in another body or on another world, typically (but not always) with memories of their prior life that will help them in their new surroundings. This is called transmigration in Chinese internet literature fandom; on the rest of the English internet it’s usually referred to with its Japanese name, isekai. In our tour through various genres next week, you’ll see that whole novels can be made out of a protagonist getting isekai’d over and over and over.

系统 (system). Another ubiquitous plot element across the gender spectrum. Many, many novels contain a disembodied force governing the protagonist’s progression through higher and higher power levels, telling them what to do next, and doling out rewards or punishments based on their performance, like a quest pane in a video game.

梗 (meme). A 梗 is not necessarily a full-fledged internet meme; it might just be a viral phrase or punchline. When a novel relies heavily on 梗s, it can be extremely difficult to translate (especially if it’s a machine doing the translating). It goes without saying that we’ll be talking about translation a whole lot later on.

The above is a starter pack of terms that apply to internet lit as a whole, but each genre also comes with its own lexicon. Fortunately, I’m standing on the shoulders of Substackers before me, several of whom have created essential guides to guide you on your wanderings through the various genres. Em over at Active Faults has for years been the authoritative source on the vocabulary of internet fandom, including fanfiction.

And Wuxia Wanderings is helpful on the varied terminology of wuxia and xianxia, much of which comes from the pre-internet era of martial arts fiction but is still useful today. (See also: Jeremy “Deathblade” Bai’s Youtube explainers.)

Way #4: as a constant cycle of satisfaction and expectation

It might seem overkill to spend so much time focusing on genre, since it seems intuitive in the abstract. But in a literary form as competitive, fast-moving, formulaic, and pared down as the Chinese internet novel, genre is fundamental to every aspect of how these novels are produced and consumed. I started to take genre seriously when I came across a series of lectures by the veteran web publisher and critic weid (real name 段伟 Duan Wei) in conversation with scholar Shao Yanjun 邵燕君, full transcripts of which are available online. For weid, genre is the art of constantly setting up and satisfying expectations, which each satisfaction laying the groundwork for the next, even higher satisfaction. A master of genre how to call on readers’ previous associations with other works to heighten their anticipation, and to deliver satisfaction in just surprising enough a fashion to keep them hungry for more. This cycle of anticipation, surprise, satisfaction, and more anticipation is not a bad working definition of shuăng.

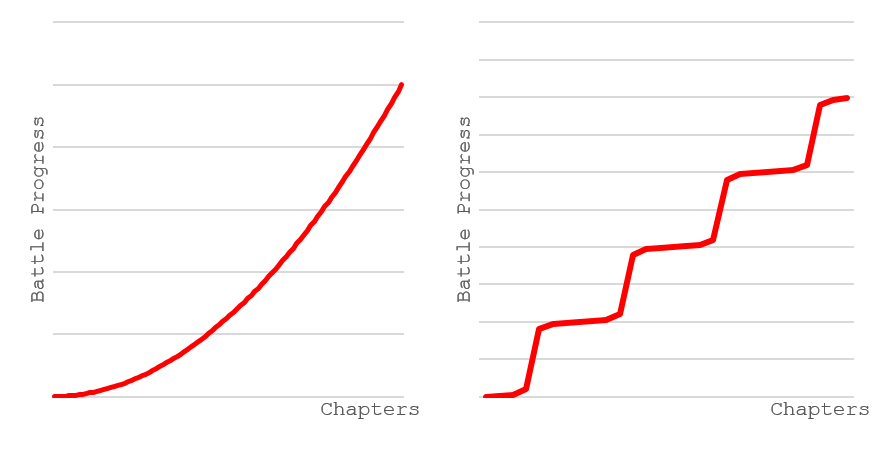

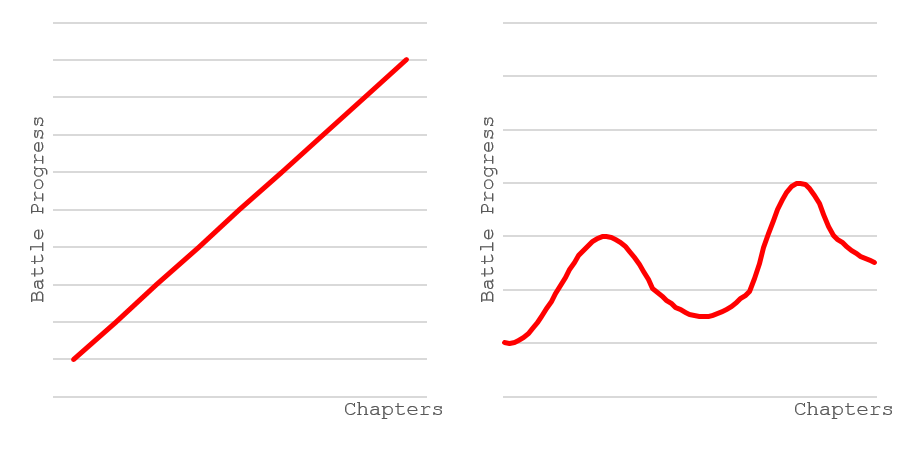

Weid’s strength as a genre commentator is that he looks at internet literature from an editor’s, not an author’s, standpoint. An author might be focused on what sets their work apart from the rest, but an editor can step back and discern how collections of unique points in individual works combine into curves that repeat again and again between stories. One of his theses is that all internet novel plots, regardless of genre, can be modeled as battles (战斗); what varies between genres are the weapons used to fight these battles and the pace at which they unfold. In a romance novel, for instance, the battle is fought with words and social politics, and an individual relationship might follow an exponential curve, at first facing seemingly impossible odds before suddenly ratcheting up to undeniable victory (below left). A plotline in a “leveling-up” story 升级文, in which the protagonist wins power and weapon upgrades video-game-style through successive campaigns, is more likely to follow a stepwise progression (below right):

Meanwhile, the basic progression of a traditional wuxia (martial arts) novel is the linear accumulation of power and abilities from start to finish (below left). And all of this differs heavily from the wavering line of traditional literary fiction (below right), with its climaxes and setbacks, which can be observed in some classic works from the early web but is greatly weakened in the current standard format of serialized, constant-satisfaction-seeking internet novels.

There’s room to criticize weid’s formulation here. His “battle progress” model of genre does not seem as well-suited to female-channel plots as male-channel ones, and it’s obvious at a glance that any story needs to borrow from all of these plot structures if it’s going to keep the reader’s attention. But what I like about his graph metaphor is how clearly it shows that the genre demands of internet literature—the need for ever more satisfying victories in each plot arc, the expectation that core genre elements will be repeated and renewed over and over again for thousands of chapters—produce a story logic that diverges from what we’re used to in traditional literature. This will be even clearer next week when we look at specific genres, many of which create shuăng through looping, gamelike plots that look almost nothing like traditional literary stories.

Ultimately, I’m willing to accept weid’s basic genre formulas because of how often internet novels are able to transcend them. In their quest to produce ever better stories, authors are constantly poking and prodding at these formulas, producing moments of unexpected delight (惊喜) in which readers’ anticipation is satisfied in just a slightly different way from what genre conventions had led them to expect. Surely the reason we have so many genres is because there are as many ways of feeling satisfied and surprised within a story as there are readers. As long as readers keep demanding moments of unexpected delight out of their stories, authors will continue to innovate, and the task of tracking genres and subgenres will become ever more futile.

But let’s try anyway, shall we?

In Part 2 of this issue, coming out in a week, I’ll give it a shot. See you then!

*Cover art source: https://openclipart.org/detail/219541/dark-vortex

Alright, fine, it was This Game Is Too Realistic 《这游戏也太现实》 by Morningstar LL (星晨LL) and translated by nonononononono and Blip for Wuxiaworld. Keep it under your hat.

You can keep dividing them into humorous and dark fourth calamity stories, apocalyptic and fantastic fourth calamity stories, harem and non-harem... There’s no bottom.

Been thoroughly following this series! and I'm only as authoritative as your average fic reader - I just write everything out loud, lol. I have a feeling you will get on to talk about 无限流 (!!) soon so I won't prod into it now, but I think the rise of that genre in particular just explains the appeal of internet lit in general. What threads all 网文 together to me is this feeling of *lack* in everyone's reality, and the sense of fulfilment you get from the idealistic worlds in your phone, be it perfect men, a world where you're the protagonist, you have "金手指" that allows you to win every single time. I guess taditional lit is also about this lack-addressing, only less satisfying and solipsistic, in total service of the reader.